Hard Problems: What are they? What's the upside to solving them in 2026?

Hard problems persist. Are they getting easier - and more valuable - to solve?

Hard Problems: One word

Shared.

Hard Problems: One sentence

Hard problems are shared global challenges - affecting millions or billions of people - where the risks and the rewards are entangled across borders, and no single actor has the mandate, money, or technology to solve them alone.

Hard Problems: One paragraph

In 2026, hard problems are the defining tests of the decade: climate transition, critical mineral sovereignty, AI safety, biosecurity, demographic shifts, planetary health, and institutional trust. They are hard partly because of technical complexity, and partly because they are entangled with legacy infrastructure, culture, and politics. No one owns these problems end‑to‑end, yet everyone is exposed to their consequences, and in many cases they remain unsolved and are worsening. They sit at the junction of public and private interest, where markets under‑provide solutions and governments cannot execute at speed and scale on their own. What makes them newly actionable is that exponential technologies (including agentic AI, edge intelligence, and digital twins) and rising soft‑power actors have shifted many of these shared challenges from impossible to plausible. Success now belongs to leaders and founders who can orchestrate across borders and sectors, rather than those who simply try to pull a single lever of hard power.

Why Soft Power and Hard Problems?

Soft power is the trust and influence you deploy, and hard problems are the shared challenges where that effort can unlock outsized strategic and commercial gains.Why this pairing?

Because in 2026, the real test of your soft power is which hard problem you choose to spend it on.Read more on Soft Power in the link below.

Hard Problems: One page

For leaders, boards, and founders in 2026, the key point is that hard problems are no longer a CSR afterthought or ‘someone else’s mandate’; they are the new frontier of strategy, capital allocation, and survival. Exponential technologies, AI agents, and global platforms have collapsed the minimum scale required to act, so a well‑positioned board and a lean founding team now draw from the same toolbox for tackling system‑scale problems. Climate risk, supply‑chain fragility, AI governance, and social instability now show up directly in revenue, cost of capital, and licence to operate. Treating these as ‘externalities’ is becoming a terminal strategic risk.

Global SDG assessments now warn that most targets are off‑track, with some reversing, which means inaction is no longer neutral - it is an active decision to ignore the massive unmet demand and systemic inefficiency that create this decade’s biggest commercial arbitrage opportunities.

Every major organisation is already in these systems, whether it acknowledges them or not: through where it sources, how it uses data and AI, which markets it depends on, and which communities it relies on for talent and legitimacy. In that sense, a hard problem is not an insurmountable obstacle; it is a high‑resolution lens for strategy - and, for some boards, the natural home for one or two genuine moonshots rather than another layer of incremental initiatives.

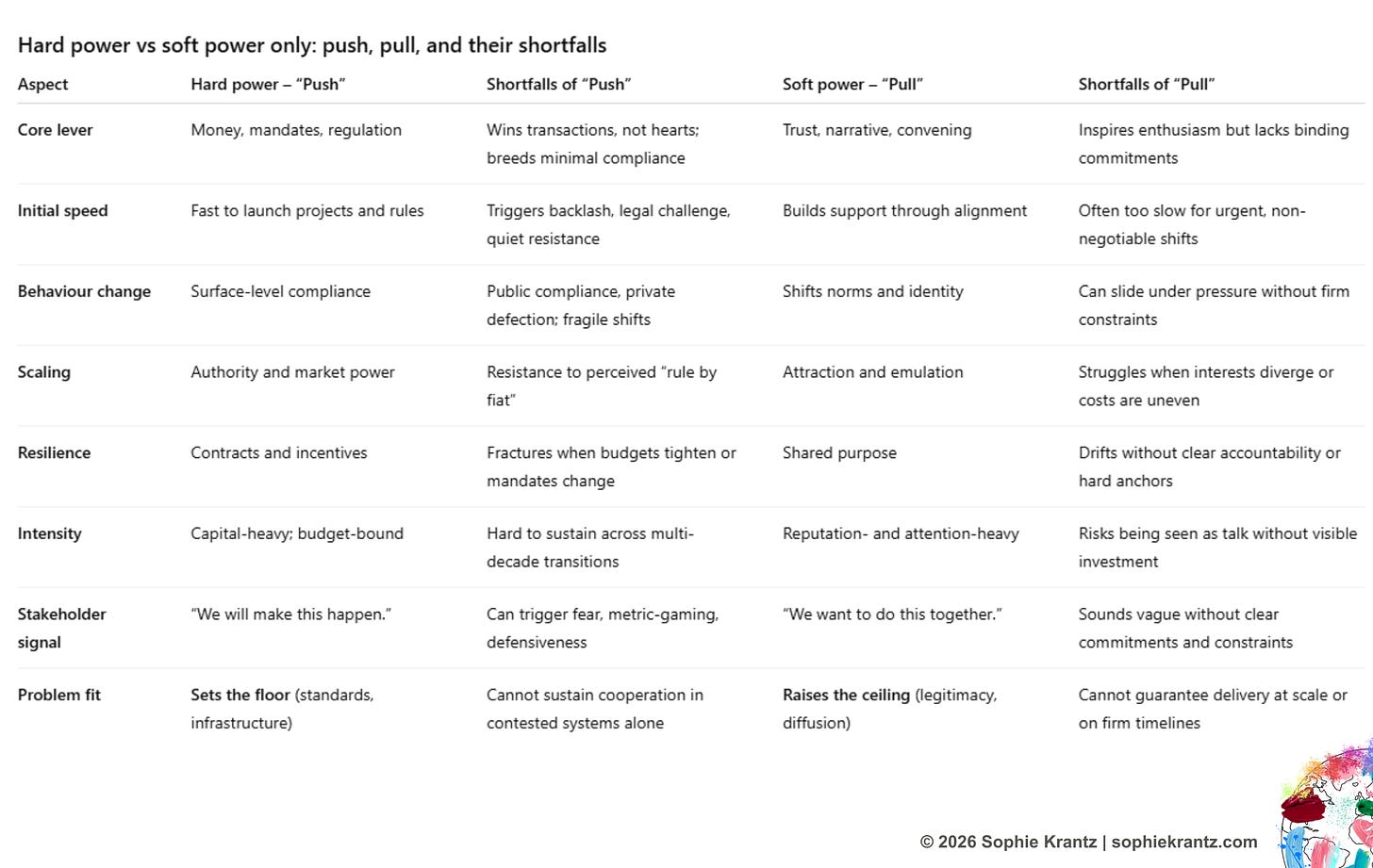

What makes a problem hard is a combination of characteristics: it spans multiple jurisdictions and sectors; it has deep path dependence (so, today’s constraints were created by yesterday’s decisions); it involves competing narratives of fairness; and it is vulnerable to non‑linear shocks and feedback loops. You cannot fix these with a single product, a one‑off capital project, or a press release. They require a portfolio of interventions over time: standards and incentives, technology and infrastructure, coalition‑building and narrative shifts. Hard problems live at the intersection of hard power (capital, mandates, assets) and soft power (trust, legitimacy, convening power). Leaders who see only one side either over‑invest in blunt force or over‑index on talk; the work is in combining both.

1. From cost centre to strategic optionality

Historically, boards bucketed hard problems as ‘regulatory risk,’ ‘sustainability,’ or ‘reputation management’ - all important, however are conceptually separate from growth and competitive advantage.

The shift in 2026 is to view them as sources of strategic optionality: new markets, new products, and new forms of resilience that emerge when you design your organisation to solve a piece of a system‑scale problem. Decarbonising a supply chain is not just compliance; it’s a play for advantaged access to future customers, talent, and green capital. Building trustworthy, well‑governed AI is not a cost drag; it is the entry ticket to high‑trust markets where opaque players are being legislated out.

In this frame, hard problems become the testing ground for your ability to generate optionality under uncertainty rather than a drag on earnings, and the few truly “moonshot‑scale” bets you take sit here as deliberate 10x plays rather than as side projects.

This optionality logic applies as much to early‑stage ventures as to listed companies: AI‑first startups are increasingly built around solving a slice of a global challenge from day one, using the same exponential tools previously reserved for incumbents.

2. Orchestrator vs builder

You do not have to become a climate‑tech lab, an AI research centre, or a health‑tech giant to work on hard problems. Many powerful technologies that used to be rare and expensive are now easy to access. Your main advantage is not building the technology itself, but deciding where you want to go and how to get there - like choosing the destination and planning the route, rather than manufacturing the car.

Boards can keep asking ‘Are we a tech company?’ - or they can stop and start asking ‘Which system are we trying to change, and what is our role in orchestrating the partners, tools, and capital to do it?’ In this role, you set direction, shape standards, and stitch together ecosystems, rather than trying to own every component. When the infrastructure already exists and the hard assets are increasingly available as services, the real constraint is no longer technology itself but the strategic focus and execution of the leaders or founders using it. The leaders who understand this shift from seeing hard problems as engineering challenges to seeing them as orchestration challenges - exactly the kind of governance shift that made Apollo‑style moonshots and today’s mission‑oriented programmes work.

For startup founders, this shift means the primary moat is often not proprietary technology however the soft power to convene talent, capital, and partners around a credible hard‑problem mission.

3. Hard problems as the ultimate stress test

Hard problems are also diagnostic. If you give a leadership team a concrete hard problem - ‘build a circular minerals loop with our suppliers,’ ‘decarbonise our logistics footprint,’ ‘embed safe AI across our customer journeys’ - and constrain them to existing assets and a tight budget, you discover their true capacity. You see who reaches first for hard spend (including headcount, budget, and reorgs) and who reaches for soft power (across coalitions, standards, and narrative). You see who understands the organisation’s soft‑power balance sheet - its trust, relationships, and convening ability - as a usable asset, and who sees only cash and control. Used deliberately, hard problems become a stress test of strategic imagination, internal alignment, and the ability to act as an orchestrator rather than just an operator, in the same way that serious moonshot programmes expose whether an organisation can sustain ambition, learning, and coalition‑building over many years.

A crucial 2026 question is then: who else has this hard problem, and where in the world is it already being solved or attacked? Instead of assuming you must build the full solution yourself, you can ask whether lower‑cost, lower‑risk, more scalable business models already exist that could solve it for you and for everyone else experiencing the same issue. That extra dimension – estimating the time and cost to solve the problem for all affected, not just for your own footprint – gives boards and founders a sharper strategic choice: is this a hard problem we should own as a mission, or are we better served by becoming a reference client and distribution partner for someone whose mission is to solve it globally?

4. Why the board or founder should care

For boards, hard problems are the most efficient lens through which to see if strategy, risk, and culture are fit for the next decade. They force zoom‑out questions: Which systems are we truly dependent on? Where are we a price‑taker, and where could we be a standard‑setter? Which coalitions are we part of by accident rather than design?

From there, they guide zoom‑in decisions: which experiments to fund, which technologies to adopt, which markets to exit, and which narratives to own. A board that can articulate its hard‑problem thesis is already ahead of competitors who are still reacting piecemeal to regulations, headlines, and activist pressure.

In this sense, hard problems are not just big headaches ‘out there’; they are the organising principle for serious leadership ‘in here’. They give you a way to align your portfolio, your technology bets, your partnerships, and your culture around a small number of system‑relevant missions, including one or two clearly defined moonshots where a 10x outcome would change your strategic position, even if the path includes productive failure and spillovers. The winners of this decade will not be those who avoided hard problems, but those who chose theirs deliberately - and built the hard and soft power to move them.

The same hard‑problem lens that helps a board distinguish where it is a price‑taker versus a standard‑setter also helps a founder decide which system to enter, and how to use a small, high‑trust footprint to punch above their weight.

Soft Power, Hard Problems

Soft power is the fuel; hard problems are where it’s finally worth spending it.

Further Reading

Hard problems, missions, and moonshots

Mazzucato, M. (2018). Mission‑oriented research & innovation in the European Union: A problem‑solving approach to fuel innovation‑led growth.

https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5b2811d1-16be-11e8-9253-01aa75ed71a1/language-enEuropean Commission – Mission‑oriented R&I policies: in‑depth case studies (Apollo, others).

https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/knowledge-publications-tools-and-data/publications/all-publications/mission-oriented-research-and-innovation-policy-depth-case-studies_enKrantz, S. (2023). “What is the global problem you could solve from where you are?”

https://open.substack.com/pub/sophiekrantz/p/what-is-the-global-problem-you-could?r=wpxa&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=webPNAS (2023). “The macroeconomic spillovers from space activity.”

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2221342120NASA History. “Managing America to the Moon: A Coalition Analysis.”

https://www.nasa.gov/history/SP-4219/Chapter8.html

SDGs and why hard problems are worsening

UN Statistics Division (2025). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025UN Statistics Division (2023). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Special Edition – Progress at the Midpoint.

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023World Economic Forum (2025). “Sustainable Development Goals: Are we on track for 2030?”

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/09/sdg-progress-report-2025Earth.org (2024). “Only 16% of SDG Targets on Track to Be Met by 2030, Report Finds.”

https://earth.org/only-16-of-sdg-targets-on-track-to-be-met-by-2030-report-findsAmnesty International (2025). “Why are the Sustainable Development Goals way off track?”

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2025/06/why-are-the-sustainable-development-goals-way-off-track

Exponential tech, agentic AI, and small‑unit agency

World Economic Forum (2025). From Safer Cities to Healthier Lives: The Top 10 Emerging Technologies of 2025.

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/06/top-10-emerging-technologies-of-2025World Economic Forum (2026). Technology Convergence Report 2025 (digest).

https://www.weforum.org/publications/technology-convergence-report-2025/digest/Google Cloud (2025). “5 ways AI agents will transform the way we work in 2026.”

https://blog.google/innovation-and-ai/infrastructure-and-cloud/google-cloud/ai-business-trends-report-2026DeepL / Press (2025). “69% Global Executives Predict AI Agents will Reshape Business in 2026.”

https://www.deepl.com/en/press-release/69_global_executives_predict_ai_agentsMicrosoft WorkLab (2026). “Agents are here - is your company prepared?”

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/agents-are-here-is-your-company-preparedRezolve.ai (2026). “One Billion AI Agents by 2026: What This Means for ITSM and Beyond.”

https://www.rezolve.ai/blog/one-billion-ai-agents-by-2026

Boards, founders, and soft power

Brand Finance (2026). Global Soft Power Index 2026.

https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-soft-power-index-2026-digital.pdfWorld Economic Forum (2026). “Next‑generation leadership can help move the world forward.”

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/leaders-wef-trust-ygl-new-kinds-of-leadersFasterCapital (2025). “The Soft Power in Startup Leadership Development.”

https://www.fastercapital.com/content/The-Soft-Power-in-Startup-Leadership-Development.htmlStartup Genome (2025). Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2025.

https://startupgenome.com/contents/report/gser-2025_4786.pdfInnovations Venture Studio (2025). “The Rise of AI‑First Startups: What 2025 Will Look Like.”

https://innovationsventure.studio/the-rise-of-ai-first-startups-what-2025-will-look-like