Terra Incognita

When does it pay to redraw the map?

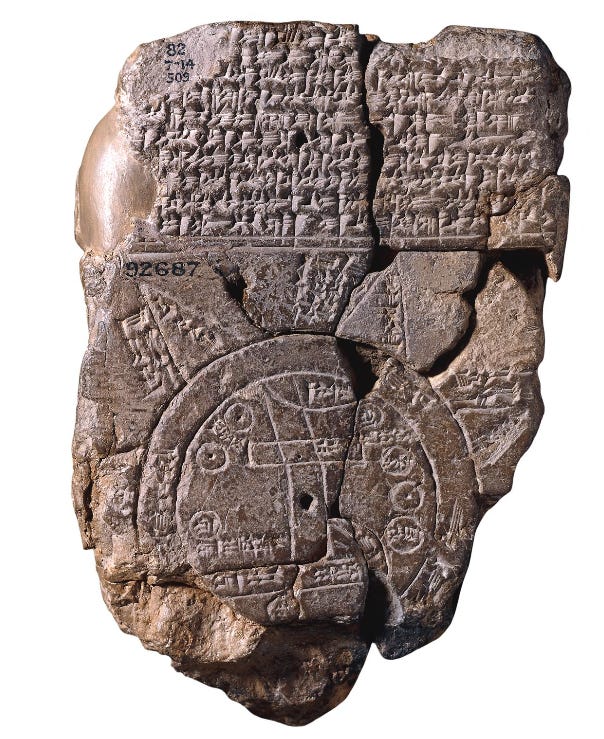

The world’s oldest surviving map was etched on a clay tablet in Mesopotamia around the 6th century BCE. Known as the Babylonian Map of the World or Imago Mundi, it shows the city of Babylon at the centre, the Euphrates River flowing through it, and the known lands encircled by a “Bitter River” - the ocean. Beyond that ring sit small triangles labelled as distant, perhaps mythical, regions.

It wasn’t so much a navigation aid, yet rather a worldview. Babylon’s placement at the centre said as much about belief as geography. The map reflected how people made sense of their world - what was known, what was unknown, and who belonged where.

Terra Incognita

Terra Incognita - Latin for “unknown land” - appeared on early European maps to mark uncharted territories. It signified both danger and discovery: areas where knowledge ended and where possibility began. We all can see leaders facing equivalent frontiers - the limits of what they know, see, and believe possible.

Over time, maps evolved with our understanding.

Greek scholars introduced geometry and latitude; medieval cartographers replaced scale with symbolism, placing Jerusalem at the centre; explorers of the 15th and 16th centuries redrew coastlines through observation; and modern satellites now chart shifting borders, climate change, migration flows, and digital networks in real time.

Each era’s map tells us what we knew and also how we saw ourselves in relation to others.

For much of history, maps offered a shared frame - a collective attempt to describe one world. Yet, that common reference is fragmenting. Leaders, nations, and institutions now operate from different mental maps: what one sees as opportunity, another perceives as threat. The same data can be read as progress or peril, depending on where you stand and which borders you recognise.

Understanding the world once relied on a shared sense of its shape and limits. Today, our technologies, algorithms, and national priorities draw diverging versions of reality. We’re no longer arguing over what lies beyond the edge of the map, yet over which map to use.

Flow, Not Friction

This short piece explores a new class of maps that go beyond territorial boundaries. These include infrastructure-maps (roads, rail, cables), population and urbanisation maps (building footprints, night-time lights), digital connectivity maps (data flows, mobile network strength) and ecosystem maps (wildlife corridors, resource flows).

By reading these maps, leaders can shift from thinking only about fixed geo-boundaries to understanding dynamic flows of people, ideas, capital and nature. These tools show where action is happening - often unnoticed - and where opportunities lie.

Mapping Our Terra Incognita

As individuals or with our teams, we can evaluate our own Terra Incognita. Today’s maps extend beyond borders - they show the movement of people, capital, data, and ideas. They reveal where activity and opportunity flow, not just where boundaries sit.

Map your worldview. What’s at the centre of your decisions - your market, your nation, your network, or humanity as a whole?

Note the boundaries. Where do you stop looking, engaging, or trading?

Identify the new cartographers. Whose maps are shaping how you see risk and opportunity - analysts, algorithms, or alliances?

Redraw with intent. Extend your field of vision into places or perspectives you’ve not yet explored.

When the Babylonians drew their map, they marked the unknown with myth. When leaders do that today - labelling what they don’t understand as risk rather than possibility - they shrink their world.

We each get to choose what we see - our worldview, and the scope of our Terra Incognita. Heading into 2026, there’s value in recognising the limits and how they restrict, delay, or reduce our wider vision for commercial success or positive-sum impact.

Shifting to Terra Cognita

What parts of the world are known to you yet unknown to those around you? What would it do for business performance (and possibly your sanity) if they had greater understanding?

What parts of the world are unknown to you, yet you have a sense that knowing more would be of value? This could be geographically- or demographically-based, data-related, or sector- or theme-driven.

Wonderful, and stimulating - I'm reflecting on danger and discovery when exploring the new!