Middle Power, Bigger Game

Australia is starting to behave like a middle power on the front line, not the sidelines, and critical minerals are the arena where that shift is most visible.

For most of the post-war era, Australia has played a relatively small economic role: a dependable supplier of raw commodities, a close US ally, and a price-taker in global markets rather than a rule-shaper. Trade and foreign policy were often framed as a choice between loyalty to Washington and market access in Beijing. Canberra leaned heavily on the alliance, accepting that decisions taken elsewhere would define prices, standards, and technologies. Critical minerals have disrupted that pattern, forcing Australia to move from a ‘quarry at the edge’ to a strategic architect within the system.

The pivot from supplier to architect

By late 2025, Canberra was using its geology, finance tools, and alliances to turn critical minerals into a national-interest lever, not just a revenue line. The October 2025 US-Australia Critical Minerals Framework set out a project pipeline of up to US$8.5 billion, with more than US$3 billion in near-term joint funding and at least US$1 billion in financing committed by each country within six months1. US EXIM alone signalled over US$2.2 billion in support via letters of interest for Australian projects2. Trilateral initiatives with Japan and Australia’s participation in the G7‑level critical minerals meeting in Washington in January 2026, show that it is competing to help design the new supply‑chain order and not just supply it34.

Hard assets, soft power, right timing

Australia’s advantage starts with hard assets: large, high‑quality reserves of lithium, rare earths, nickel, and manganese essential to the green transition and defense supply chains5. It is pairing those assets with a stronger mix of soft‑power tools - regulatory reliability, alliance compatibility, and tight ESG standards - to position itself as the trusted partner of choice for allies67.

In this geoeconomic reality, ESG has become the price floor for market entry; however, Australia’s ‘clean and clear’ branding offers a higher ceiling: supply chain security. By integrating its mineral wealth into allied industrial frameworks and security architectures, Australia is moving beyond the role of a bulk exporter to become a reliable backstop for supply. For global partners, the value proposition shifts beyond the quality of the ore to the certainty of the origin and the durability of the partnership in a fractured world.

G7‑aligned manufacturers are buying material they can stand behind in front of auditors and regulators. Canberra’s critical minerals reserve model - centered on future production agreements rather than physical stockpiles - locks in long-term offtake with allies while signaling financial innovation8. G7‑aligned ministers are now openly debating price‑support tools and ‘green premium’ dynamics for critical minerals, and Australia is pushing to ensure that cleaner, higher‑cost supply is not undercut by opaque, subsidised alternatives - even when markets are volatile9.

The timing is favourable. China’s export controls on key inputs, combined with US‑led friend‑shoring, have pushed critical minerals to the centre of the new global trading system. For middle powers with both resources and credibility, this creates a window of leverage that rarely appears, because supply stress, great‑power rivalry, and rule‑writing for a new system do not often converge at the same time.

Not bowing to the US, not provoking China

The new play appears to not be about choosing Washington over Beijing. Rather, it is about widening Australia’s room for manoeuvre. On one side, the US partnership has deepened: the 2025 framework, the US$8.5 billion project pipeline, US EXIM and Export Finance Australia co-financing, and joint investment targets embed Australian projects within US and allied industrial ecosystems. On the other, Australia has deliberately stopped short of a ‘China-free’ strategy. China remains its largest trading partner, and policymakers frame their moves in terms of resilience, national interest, and diversification, not containment10.

Canberra’s handling of the Darwin Port lease shows this in practice. Security reviews have found no current basis to overturn the 99-year lease and so the Albanese government has tightened oversight and signalling rather than forcing divestment11. The message is clear: future strategic infrastructure deals will face a harder test on security and sovereignty, yet corrections will be managed through institutions and national-interest reviews, not headline-driven rupture. This balanced approach matters inside Australia. Chinese trade reprisals during the Morrison era hit sectors such as beef, barley, wine, and lobster, and are widely understood as a warning against headline‑driven confrontation that leaves exporters carrying the cost12.

Processing hurdles and social licence

The move from shipping ore to shipping chemicals - sulfates, hydroxides, and refined rare earths - faces real technical and economic headwinds. Australia must compete with heavily subsidised Asian processing hubs while carrying higher energy costs, complex environmental approvals, and a shortage of specialist metallurgical and processing talent1314. Analysts point to critical skills gaps in advanced metallurgy, process optimisation, and environmental compliance as major bottlenecks, alongside the cost of building plants that meet both domestic and international ESG expectations. In response, Canberra is leaning on a mix of migration settings, training, and regional incentives to attract and grow specialised talent across energy and resources, including critical minerals.

Social licence is becoming a strategic variable, not a footnote. Parliamentary inquiries launched in late 2025 explicitly link critical minerals to regional development, Indigenous engagement, and job creation, framing community consent as a precondition for durable growth. State strategies, such as New South Wales’ 2024-2035 Critical Minerals and High-Tech Metals plan, forecast thousands of construction and ongoing jobs in regional areas and position critical minerals as a backbone of local economies1516. That domestic coalition across regional jobs, skills growth, and royalties gives the national strategy staying power. It is harder for future governments to walk away from projects that are visibly anchoring the economies of WA, QLD, and NSW.

Ambition and agency in critical minerals

Australia’s response in critical minerals over 2025-26 shows greater ambition and agency than in earlier commodity cycles. It is designing a strategic reserve, shaping forward contracts and price-support mechanisms, and actively courting US, Japanese, EU, and Korean investment into onshore processing, rather than waiting for global prices to dictate outcomes17. It is also embedding critical minerals into high‑level diplomacy - from the US framework to EU FTA talks and G7‑level discussions - so projects and offtake rest on political commitment as well as market demand18.

A low-ambition, low-agency response would look different. Australia would continue exporting unprocessed ore to the highest bidder, leave processing and technology to China and others, and treat US or EU initiatives as optional extras rather than co-designed frameworks. It would avoid the complexity of strategic reserves, shy away from price-support mechanisms or forward contracts, and accept that supply-chain security, standards, and innovation were someone else’s responsibility. In that world, Australia would remain a quarry with little say over downstream value, exposed to price swings, export controls and great‑power bargaining.

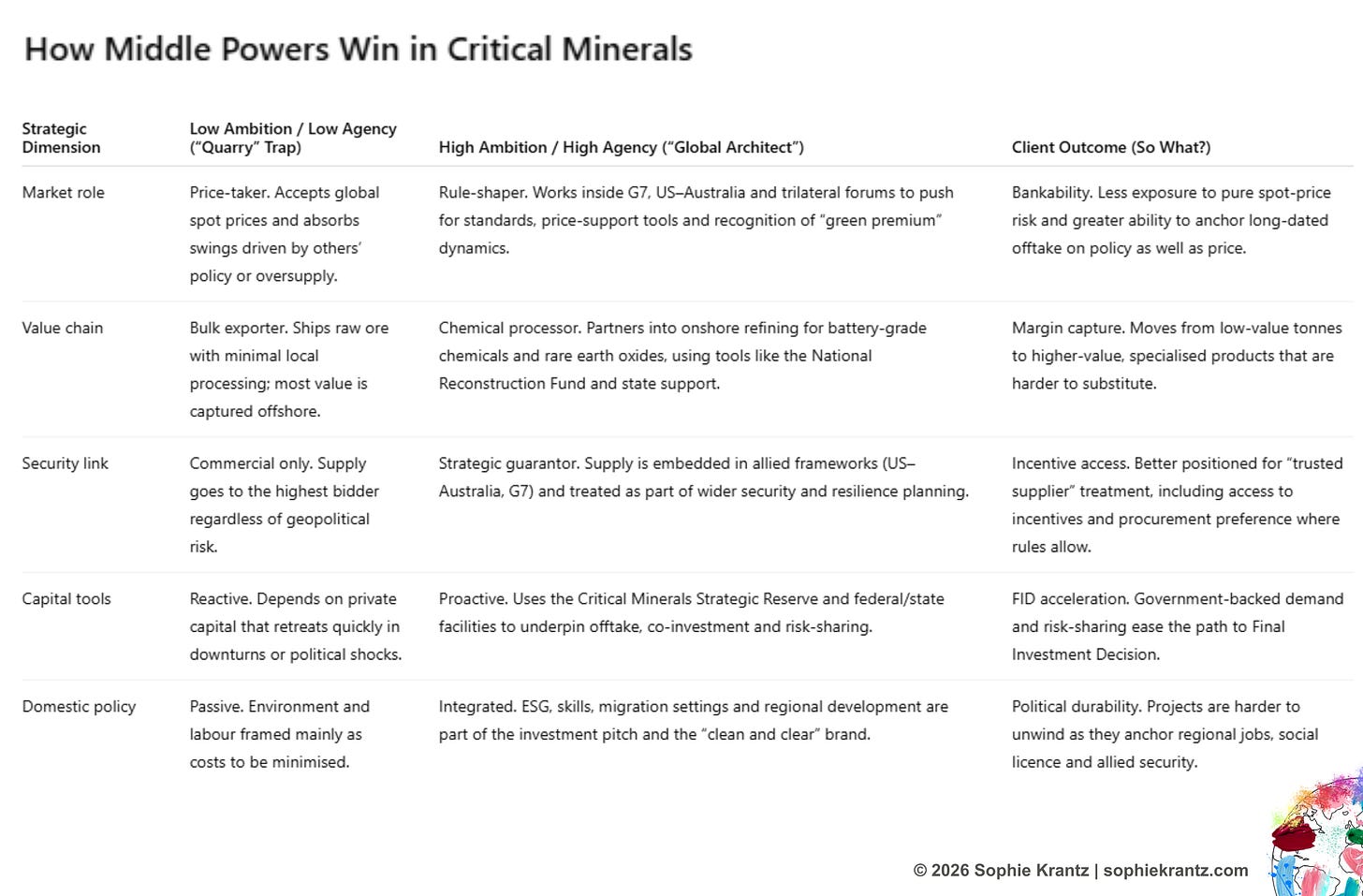

Seen through this Ambition × Agency lens, Australia has clearly shifted up the curve in critical minerals. I use the same diagnostic with clients to identify where a sector or firm is currently a passive price-taker - and where there is a window to pivot into a shaper role before the window of leverage closes.

Read across the rows in the table below and you have the Ambition × Agency map I use with clients: a fast way to see whether you’re still in the quarry trap, or starting to behave like an architect in your own system.

Designing the market: soft power, hard problems

What distinguishes the current moment is that Australia is beginning to use soft power to tackle a hard problem: how to de-risk a fractured system by pairing assets with alliances, norms, and market design. The Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-2030 speaks in the language of ‘diverse, resilient and sustainable’ supply chains. Canberra is signalling that it wants to be seen as a problem‑solver for the green transition, not a passive recipient of investment. In G7-aligned forums and trilateral work with Japan and the US, Australia has consistently argued that ESG-compliant supply should not be undercut by opaque, high-emissions material, and that standards, traceability, and financing tools must reflect the real cost of ‘clean and clear’ production19.

What does this mean?

For investors, this creates a de facto green-premium logic: projects demonstrating compliance, security, and social license are better placed to secure long-dated offtake and concessional finance - even if headline costs are higher.

For policymakers, it means a seat at the table where standards and informal rules are shaped rather than imported.

For manufacturers, it offers a credible path from shipping dirt to shipping chemicals that plug directly into G7-aligned value chains.

For leaders, it is a live case study in how soft power and positioning can turn hard constraints into strategic leverage, rather than just more risk.

For a middle-sized economy, this is what playing a bigger game looks like: using soft power, hard assets, and diplomatic persistence to tilt emerging trade rules toward outcomes that last beyond any one president, any one government, or any one price cycle.

This is one case study in a bigger argument about how the “rules‑based order” is giving way to value‑based, middle‑power systems. I explore that wider shift in From Rules-Based Fiction to Value-Based Realism: A 2026 Playbook.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/united-states-australia-framework-for-securing-of-supply-in-the-mining-and-processing-of-critical-minerals/

https://www.exim.gov/news/exim-powers-america-first-22-billion-critical-minerals-commitments-secure-supply-chains

https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/us-and-australia-deepen-critical-minerals-engagement-to-counter-china/

https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/international/us-urges-partners-and-allies-increase-critical-minerals-supply-chain-resiliency

https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/critical-minerals-strategy-2023-2030

https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/king/media-releases/australia-joins-global-commitment-esg-critical-minerals

https://www.pmc.gov.au/domestic-policy/critical-minerals-strategic-reserve

https://smallcaps.com.au/article/australia-establish-strategic-critical-minerals-reserve-global-trade-tensions-rise

https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/news/australia-price-floor-critical-minerals/

https://www.ussc.edu.au/australias-economic-security-outlook-trends-and-possible-responses-for-2026

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2026-01-30/farmers-urge-careful-diplomacy-in-darwin-port-row-with-china/106288346

https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-morrison-legacy-beyond

https://discoveryalert.com.au/australias-critical-minerals-processing-challenges-2025/

https://australianminingreview.com.au/issue/2026/01/profits-up-jobs-down-the-resources-sector-paradox/

https://www.nsw.gov.au/regional-and-primary-industries/critical-minerals-and-high-tech-metals-strategy-2024-35

https://www.investregional.nsw.gov.au/opportunities/our-globally-competitive-industries/critical-minerals

https://www.csis.org/analysis/unpacking-us-australia-critical-minerals-framework-agreement

https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/9168697/eu-trade-deal-inches-closer-amid-minerals-talks/

https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/sustainable-critical-materials-cant-have-a-price-premium-without-global-standards/