From Rules-Based Fiction to Value-Based Realism: A 2026 Playbook

In Davos this year, Mark Carney stated what many have been working around for some time: the rules-based international order no longer functions as advertised. His call was for “value-based realism” - an approach that accepts rupture as the baseline and treats resilience as something to be built deliberately rather than assumed1.

For any organisation that relies on global markets, global supply chains, or global capital - particularly those anchored in middle-power economies - 2026 is not a year to wait for stability to return. It is a year to redesign trade, investment, and operating decisions on the assumption that shocks, fragmentation, and negotiation-by-exception are now normal.

UNCTAD’s 2026 outlook, highlighting 10 top trends redefining global trade this year, reinforces this point. Slower growth, rising tariffs, value-chain reconfiguration, and new digital and green rules are reshaping trade for firms across all regions and sectors2. Exposure is structural, rather than geographic.

1. The rules no longer protect you

Carney’s argument is clear. Continuing to invoke a “rules-based international order” as a reliable safeguard bears risk. Great powers are openly using trade, finance, and economic integration as tools of statecraft. Tariffs, export controls, sanctions, and investment screening are applied selectively and adjusted in real time.

Value-based realism is the middle-power response. It does not reject values or alliances. It insists on clarity about them, while being pragmatic about counterparties, diversification, and where risk is actively managed rather than denied.

For firms, this changes a long-standing assumption. Compliance alone no longer buys safety. What buys room to operate is soft power: credibility, trust, usefulness, and relevance within the right networks. Soft power has become an operational capability for dealing with hard constraints such as sanctions creep, export controls, carbon border measures, and sudden tariff shifts3.

2. MC14 is a hinge, not a solution

The WTO’s 14th Ministerial Conference (MC14) in Yaoundé, Cameroon, on 26–29 March 2026 will be presented as an effort to stabilise multilateral trade. Dispute settlement reform, agriculture, digital trade, and climate-linked measures are on the agenda. These are the technical foundations that determine whether trade rules remain enforceable and usable, particularly for smaller and mid-sized economies4.

UNCTAD describes 2026 as a crossroads. Global growth is expected to sit around 2.6%, trade growth between 2.5-3%, while unilateral tariffs and economic-security measures continue to affect investment and supply-chain decisions. Whether MC14 delivers progress on the Appellate Body, policy space for industrialisation, and clarity on digital and climate rules will influence whether multilateralism still underpins development strategies or continues to erode.

For boards and executive teams, the tempting question to ask is: “will MC14 fix the WTO?” Perhaps the more valuable question is: “what happens to our disputes, market access and regulatory exposure if it does not?” That requires a focused audit: which revenue streams rely on enforceable WTO rules, which rely on unilateral preferences, and where exposure is highest if defensive measures continue to escalate.

3. Where rules are being written now

While ministers gather in Yaoundé, much of the practical rule-making is already happening elsewhere. Mega-regional and digital-first agreements such as CPTPP, RCEP, and the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) are becoming the venues where digital, services and sustainability rules are updated when multilateral processes stall.

UNCTAD’s 10-trends snapshot highlights three shifts with direct implications for operating models:

Trade rule reform is at a decision point. Outcomes on e-commerce, services, and digital transactions will shape how digitally deliverable services and servicification evolve.

Tariffs and non-tariff measures, including carbon and deforestation rules, are being used strategically. They increase compliance costs while favouring firms that can demonstrate low-carbon, traceable, and high-integrity supply chains.

Supply-chain reconfiguration and growth in South–South trade are opening new corridors across Africa, Latin America, and Asia for firms that can operate across overlapping regimes.

The leadership question to ask today is: if the ‘rules’ in our key markets were suspended tomorrow, what irreplaceable utility would our organisation still provide to the resilience of those partners - and how are we using that leverage to co‑author the ‘private rules’ of our specific corridor?

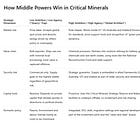

4. Critical minerals show value-based realism at work

Critical minerals provide a current example of value-based realism in action. Demand for transition metals remains strong, even as prices, bargaining power and policy settings swing sharply, and trade, finance and security considerations become tightly intertwined.

In late 2025, the US–Australia Critical Minerals Framework moved from concept to implementation. Joint mechanisms such as a Supply Security Response Group, alongside early project-financing commitments, signalled a clear willingness among allies to deploy capital in support of security-driven supply-chain strategies. At the G7 finance ministers’ meeting in Washington on 12 January 2026, with Australia and India at the table, rare earths and critical minerals were treated as shared security assets, with discussions centred on coordinated financing, stockpiles and diversification away from single-supplier dependence.

For Australian and regional firms, this shifts project logic. Advanced processing and value-added manufacturing - from gallium and rare earths in Western Australia to battery-grade materials and recycling - are no longer assessed on IRR alone. Their contribution to allied resilience and strategic autonomy now shapes access to capital, offtake and policy backing. That, in turn, influences partner choice, project framing and coalition alignment - whether through US-Australia-Japan arrangements, G7-plus initiatives, or emerging Indo-Pacific and South–South groupings.

It also shows how a middle power can exercise agency through soft power. As Australia deepens trade and investment ties with partners such as the US and Japan and deliberately moves up the critical-minerals value chain to diversify beyond pure commodity exports, it has also maintained close economic links with China, its largest trading partner. That choice marks a departure from the Morrison era. The combination of credible security partnerships, economic openness, and pragmatic diplomacy turns a hard-problem sector like critical minerals into a platform for influence rather than vulnerability.

Read more here:

5. A 2026 playbook: Soft power, hard problems

Carney’s speech and the 2026 trade calendar point in the same direction: organisations that rely on global systems cannot afford to remain passive rule-takers. In a world of weaponised trade, fragmented rules, and rewired value chains, soft power is no longer a reputational bonus. It is how options are created, coalitions are held together, and hard problems are worked through when no single actor is in control.

Soft power becomes useful when it produces agency. Values without leverage change little. What matters is whether your organisation is trusted, credible, and relevant enough to influence outcomes when rules are bent, exceptions are negotiated, or capital is selectively deployed. This is where firms either gain room to move - or discover they have none.

This shift is operational. The table below shows the change in assumptions now shaping trade, investment, and supply-chain decisions. What once optimised for efficiency is now judged on resilience. What relied on rules and compliance now depends on coalitions, credibility, and alignment. Firms still operating to the old logic are not wrong; they are exposed.

Value-based realism, in Carney’s terms, asks middle powers to be honest about power while refusing to abandon their values. The same applies to firms. Soft power turns into a strategic asset when it is used to convene coalitions, anchor standards, and co-design workable arrangements across blocs - reducing exposure to shocks while increasing the ability to act.

This is the work I do with clients: helping boards and executive teams that rely on global markets to turn soft power into concrete agency, by redesigning trade, investment, and supply‑chain choices for this new, value‑based realism.

The critical-minerals example shows this in practice. Australia has deepened security and investment ties with partners such as the US and Japan, deliberately moved up the value chain beyond pure commodity exports, and maintained economic links with China, its largest trading partner. This is not indecision. It is deliberate positioning. Credible security partnerships, economic openness and pragmatic diplomacy turn a hard-problem sector into a platform for influence rather than vulnerability. Firms face the same test.

A practical 2026 checklist for leadership teams using soft power to tackle hard problems:

Re-rank your counterparties, not your talking points. Map customers, suppliers, financiers, and regulators by (a) values and standards alignment and (b) practical leverage over your risk and growth. Prioritise relationship-building and information-sharing where both are high.

Run a shock-scenario audit, not a generic risk review. Stress-test your portfolio against three concrete shocks: a stalled MC14 (i.e. persistent WTO weakness), a new unilateral tariff or carbon measure in a key market, and a sudden export-control move affecting a critical input. For each, identify which coalitions, exemptions or alternative South–South corridors you would rely on - and whether they exist today.

Turn one strategic bet into a coalition asset. Select a single project - in minerals, green supply chains, data, or services - and design it deliberately to strengthen the resilience of a wider network, whether an allied supply chain, a regional digital platform or a standards initiative. That positioning makes it a credible candidate for blended finance, policy backing, and preferential treatment.

Be the counterparty others need in moments of stress. Carney warns that middle powers absent from the table risk ending up on the menu; the same applies to the organisations within them. In 2026, soft power is not about attending more meetings. It is about how you show up during shocks, how you design for shared resilience, and how you convert credibility into influence.

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2026/01/davos-2026-special-address-by-mark-carney-prime-minister-of-canada/

https://unctad.org/publication/global-trade-update-january-2026-top-trends-redefining-global-trade-2026

https://unctad.org/news/10-trends-shaping-global-trade-2026

https://twn.my/title2/wto.info/2026/ti260108.htm